I often wish that I could remember more about what went on in lessons when I was at school. There are snippets that I can recall quite well: I can remember learning to balance quadratic equations, memorizing the periodic table and about the history of WW1. One thing, though, that I cannot remember – no matter how hard I try – is how I learnt to write.

In fact, I’m almost definite that in my school, we were not explicitly taught grammar and sentence structures. One reason that I know this is that as a trainee teacher, I had to learn this myself. The question, then, is how is it that I know how to write? I have a hunch that I learnt how to write through reading, but how do I help people learn to write who – on the whole – read less than I did?

For me, the explicit teaching of the structural content (sentences, features etc.,) of writing has been a vital part of helping my students to write well. In this post, I will discuss the evolution of my practice in this area, critiquing each method I have used, before arriving at one that I consider effective.

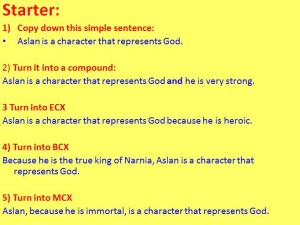

1) The sentence variation starter #1: When I first started thinking about improving my students’ sentence writing abilities, the first thing I used, along with many of my colleagues and, I imagine, teachers the world over, was this:

I taught students how to write using simple (S), compound (C) and three kinds of complex sentence (moving the subordinate clause to the beginning (BCX) middle (MCX) and end (ECX) of the sentence). To download my lesson on how to teach students to do this, click here: Lesson S C ECX BCX MCX.

At the start of every lesson, I gave students a simple sentence that related in some way to our content for the day. They had to transform it into the four other types. My hope was that by the constant, repetitive practice, students would begin naturally to use these kinds of sentence in their writing.

Problems:

When students engaged in extended writing, they would, generally resort to the same patterns (or lack of) as before we began intensive practice of the five sentence types, I think for the following reasons:

- The fantastic book ‘Make it stick: The Science of Successful Learning’ finds that deep learning comes when practice is done in the same context as performance. For example, if a musician sits at home and practices the scales all alone, even to a high level of expertise, they will be lost in a real life performance situation when mastery requires so much more. Or, to put it another way: ‘If you always practice the same skill in the same way, from the same place…you’re starving your learning on short rations of variety.’ By making the context and conditions of practice exactly the same, every lesson, students were not actually able to use their learning in any other context than as part of a lesson starter.

- This book also states that ‘Effortful retrieval makes for stronger learning and retention.’ Now, while having the same starter lesson after lesson certainly asks students to repeatedly retrieve the information, is it actually effortful? Is performing the same thing, multiple times per week a challenge? I would argue that the grammar starter, if repeated in exactly the same way is not challenging enough to encourage real, long-lasting learning. David Didau’s ‘Learning Spy’ blog argues that this sort of practice is in fact an example of performance rather than learning: this sort of ‘massed practice’ means that students become adept at performing under certain conditions, rather than making real progress.

So, what did I learn?

- Repetitive grammar starters, isolated from real writing, are pointless. Students need to practice their grammar in the same arena as I would expect them to perform: in real pieces of writing.

- Recall of the material needs to be made more challenging: asking students to repeat the same knowledge, in the same way, in the same part of the lesson means that they become trained to perform in a certain way. They actually learn very little.

- In fact, would I even be satisfied if students were only able to use five kinds of sentence structure? I felt that I needed to demonstrate higher expectations of my students by asking them to master many more structures and features.

2) The Sentence Variation Starter #2: The next thing that I tried was to compile a larger variety of sentence types – a list that I called ‘The Big 15’–and have the students utilise them in a real writing context. The list contained the five sentence types above, as well as others that I took from Alan Peat’s ‘Exciting Sentence Types’ resource. This contained sentences such as:

- Some; Others – The first part of this sentence begins with the word some. The second part of the sentence is separated with a semi colon and the word others. Some children walk to school; others travel by car.

- Starting a sentence with a simile – using a simile, followed by a comma, as the first clause of yours sentence. Yawning like a lion, he sat up.

My ‘Big 15 sentences’ sheet can be downloaded here: The Big 15

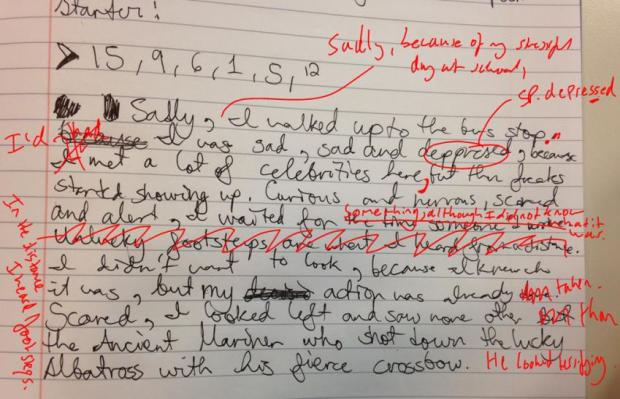

Alongside this list, which students stuck into the front inside cover of their books, I created a lesson starter called ‘At the Bus Stop’ (actually, I stole this from a primary school that I visited). As the class was working on descriptive writing at the time, at the start of every lesson I asked students to imagine meeting a different person at the school bus stop. They had to describe this encounter using a specific set of the big 15 sentences, selected through random numbers (1, 14, 5, 6, 3, 11 etc.,). This ‘Slow Writing’ approach was heavily influenced by David Didau’s blogging, found here and here.

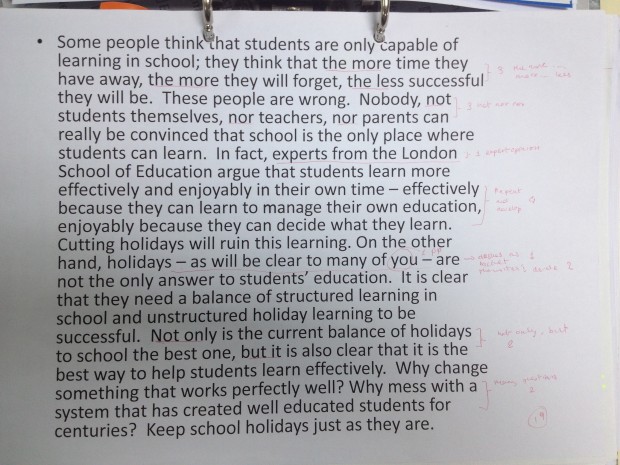

I then asked students to read and assess each other’s descriptions, before giving them time to revise and edit their work. This is an example of a student’s piece of writing for the above task, with revisions made on the board:

Problems:

This was a far more successful experiment. There were clear improvements in student writing across the board, and students actually enjoyed their starter far more than the previous one; it also linked in much better with our lessons. There were, however, still some issues with this approach:

When I assessed students on their descriptive writing, while there was a marked improvement in sentence variation, some students used a disappointingly small number of the sentence types, and all had issues ‘blending’ these with descriptive features. While I had made improvements in asking students to practice in a more realistic context, I had not concentrated on actually asking them to learn and retrieve the key knowledge.

Another quotation from ‘Make it Stick’: ‘Effortful retrieval both strengthens the memory but also makes the learning pliable again, leading to its reconsolidation.’ My students had become reliant on the Big 15 sheet as a crutch in their writing, and I, as their teacher, had not known enough to concentrate just as much on the students’ memorisation of the sentence types as I had on their ability to use them. Retrieval of the knowledge was effortless; hence, learning was limited.

What did I learn?

- Again, I needed to make recall of the material more challenging. I could have included periodic tests on the sentence types and I could have removed the Big 15 help sheet after a certain period of time.

- Another insight from ‘Make it Stick’: Rather than mixing up the writing styles that students were practicing (interleaving descriptive writing and its constituent sentence types and features with other writing styles, for example), I concentrated only on one writing style, leading – or so says the evidence presented in the book – to suboptimal learning: ‘…the research shows unequivocally that mastery and long-term retention are much better if you interleave practice than if you mass it.’

3) My current project:

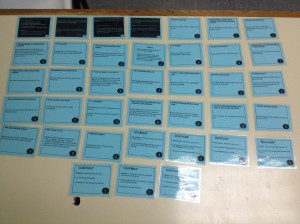

Inspired by the ‘Learning from My Mistakes’ post, ‘Death to the Sentence Stems: Long Live the Sentence Structures’, from which I took nearly all the sentence structures to follow, I decided to make my expectations of student writing much more challenging. I created sets of cards – one set for descriptive writing, and one set for argumentative writing – containing all the success criteria ( not only sentence structures but language features, structural elements like connectives and key expectations, like using clear topic sentences) for each style. I also attached points to these, so for example in descriptive writing:

- A Personification, 5 commas and 3 tos sentence: ‘Harsh white walls frown at the monotone uniformed prisoners, men with bleached faces and no eyes threaten, guns hoover, thunderously muted, waiting for someone to move, to think, to breath.’ is worth 4 points.

- A Comma sandwich (MCX): ‘The sun, which had been absent for days, shone steadily in the sky’ is worth only 1. These are awarded based on the difficulty (or flashiness) of the sentence.

- Using onomatopoeia, or any other descriptive feature, is worth 1 point.

- Failing to meet certain fundamental expectations for the style, like using a mixture of short and long sentences, or clustering descriptive features to create vivid imagery, deducts 5 points.

While in argumentative writing:

- A Not, nor, nor sentence: Nobody, not the postman, nor the housekeeper, nor Jim himself knew how the letter had got onto the doormat. is worth 3 points

- Use of imperatives or any other argumentative feature is worth 1 point.

- Failing to use connectives to link ideas and paragraphs appropriately results in a loss of 5 points, amongst a variety of other key stylistic expectations.

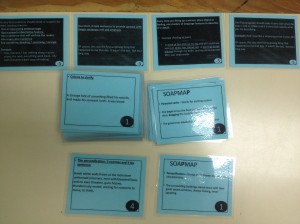

In both sets, there were roughly 35 cards overall, with around 20-25 sentence structures, the rest being made up of features or key stylistic expectations. A full set can be seen below; the black cards are the key expectations, which remain laid out at all times. The others are either structures or features, which are shuffled and placed in separate piles.

The set of cards for descriptive writing can be downloaded here:Cards – Describe , and for argumentative, here: Cards – Argue.

How did I use the cards (the steps):

- Familiarsation: I began to use the cards in paired writing activities. A fantastic discussion of the benefits as well as a successful structure for paired writing can be found on the Reflecting English blog. Students worked in pairs, each directing the writing of the other by selecting two cards: one sentence structure, and one feature. The students would work to combine these in their writing, asking their partner to check their attempt for correctness before requesting another pair of cards. The image below shows a game being played; the two bottom cards are in active use; when finished with they are placed to the back of the piles.

- Memorisation: After familiarising themselves with each card through the paired writing process (this took a couple of lessons), the students then went about memorising the cards. This was done through using them as flashcards, with students looking at the title of the card and having to recall and write an example. Cards that they could complete went on one pile, and those they couldn’t on another, continuing until all cards had been successfully recalled. From ‘Make it Stick’: ‘Something as simple as a deck of flashcards can provide an example of spacing. Between repetitions of any individual card, you work through many others.’ I think, therefore, that this method, giving the sheer number of structures and features to commit to memory, fulfills the criteria for a ‘desirable difficulty’, especially when you interleave two different writing styles, which I did. My students found this hard!

- Testing: At this point (after leaving a gap of a couple of days), I removed the cards completely and introduced low-stakes testing to aid recall of the structures and features. Previously, I would have continued with students continually using the cards in their writing until I felt they were comfortable with them. Evidence says this is incorrect; again from ‘Make it Stick: ‘Today, we know from empirical research that practicing retrieval makes learning stick far better than reexposure to the original material.’ I used a Quizlet page for the testing (writing to describe here; writing to argue here. This is the easiest tool I know of for quickly making randomised tests). Students then used the cards to relearn material they had forgotten. I repeated this step a couple of times, interleaving the describe and argue tests to build the level of difficulty.

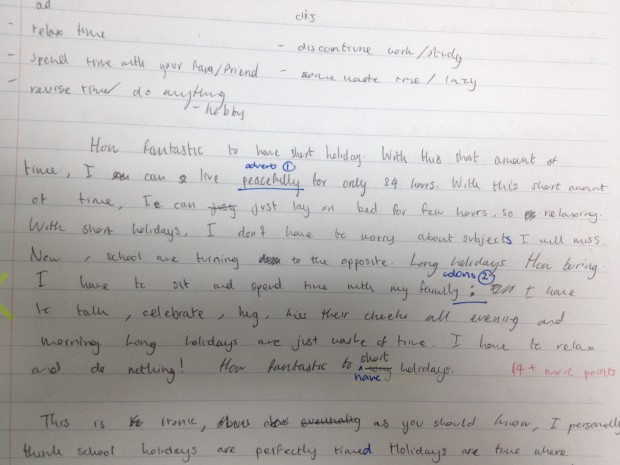

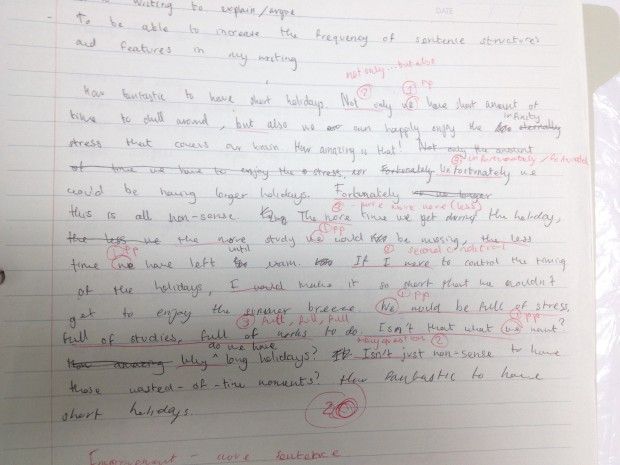

- Writing without prompts: I then gave students a writing task to complete without the aid of the cards. This served as another test with an even higher level of difficulty as they didn’t even have the names of the sentences and features to act as prompts, something that students found fairly taxing. Knowing that they were trying to achieve a certain score in their writing helped to provide impetus to recall the material, even when effortful.

- Modelling, peer assessment and improvement: Following this, I showed the class a model that I had written using the cards, asking the class to score this:

The idea of scoring the model was to show the students the quantity of sentence structures and features that a high quality paragraph might contain. There is obviously no hard and fast rule here: the idea of scoring writing can seem a little formulaic but I wanted the students to see that good writing is, in the main, packed with interesting sentence structures and features (students scored my paragraph at around 19 points).

Next, I asked students to read their partner’s work, picking their best and worst paragraphs and scoring them in the same way. Here is an example of a student’s ‘worst’ paragraph (it achieved 4 points):

Finally, student re-wrote their paragraphs, attempting to bring them closer to the score achieved on my model. Again, this was done with no prompting from the cards, and achieved a 16 point increase, demonstrating, I think, the power of adding some sort of a ‘stake’ to a test: the simple desire to want to beat their own score increased effort and improved recall. This is also just the sort of effortful recall that leads to long term memorisation.

Now, it goes without saying that I repeated these steps quite a few times, especially the testing, modelling and peer assessment stages. I was also very careful to interleave each writing style –both with each other and with other completely different topics. I hope this meant that I was leaving enough of a gap for optimal ‘forgetting’ to occur before returning to the material. This method has, without a doubt, done more to help my students produce excellent writing than any I’ve ever used before.

Benefits of this method:

- At every stage, students found it really, really hard, but this is a good thing. As Didau writes: ‘Deliberately choose the harder, more difficult option. Learning isn’t easy. But as Hattie reminds us, “A teacher’s job is not to make work easy. It is to make it difficult.”

- Rather than just sentence structures, language features or any other criteria, it encompasses all of these together. This means that students have to be able to recall and master multiple things at once, as well as worrying about content, something that expert writers can do but that is a hugely challenging thing to grasp.

- Unlike with grammar starters, students practice their writing in a ‘performance context’: they create real pieces of writing, without aids or prompts, just as they would in an exam situation.

- It is easy to test students on their abilities, and easy to judge real progress being made over time.

- It creates pieces of writing that score highly in exams. Examiners like interesting structures and features, combined in unique ways.

- It privileges knowledge over skills: students need to learn the content before they can use this in writing. Put simply, there is no such thing as the skill of writing; it is just a case of mastering a vast network of different areas of knowledge. This method recognises that fact.

Once again, for download, my cards for argumentative and descriptive writing are here: Cards – Argue, Cards – Describe.

Further reading: in no particular order, here are some of the things that I read which helped me in my thinking about writing.

- Make it stick: The Science of Successful Learning, by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III and Mark A. McDaniel.

- Reflecting English: The Beauty of Paired Writing

- Learning from My Mistakes: Piddle, PEE and WEE

- Learning from my Mistakes: Death to Sentence Stems – Long Live Sentence Structures

- The Goldfish Bowl: The Art of the Sentence

- Teaching, Leading Learning: It’s not skills – It’s know how.

- The Learning Spy: Deliberately Difficult – Why it’s better to make learning harder

- The Learning Spy: The Problem With Progress – Designing a curriculum for learning

- The Learning Spy: How Slowing Down Can Improve Your Writing

- The Learning Spy: Revisiting Slow Writing

#1 by Fin Gall on June 17, 2015 - 9:18 am

Great post, JG.

I like how you’ve refined how pupils practise writing, from a straightforward, repetitive mode to one that is challenging, alert to different contexts and which relies on applying knowledge. I thought it was interesting that you found pupils’ learning effectively stopped when they were asked to perform and perform again a relatively limited pool of writing skills, such as working with the initial sentence types. I think the analogy of only practising at home in safe comforts being restrictive in comparison to practising in a range of contexts with clear links to a final performance (like a concert, so for a pupil an assessment or exam), is a very useful one. It helps to give a rationale for timed tasks, closed book activities etc. I can imagine using this idea to explain the importance of exercises for pupils to develop their metacognition.

Lots of useful links to other blogs too. Thanks for your Big 15 resource: I’m looking forward to using this in the classroom from September.

Fin