Rigorous Analytical Writing: Is P.E.E fit for purpose?

In my relatively short teaching career (two schools; two countries; five years), I have been exposed to a vertiginously long list of different strategies, acronyms and procedures for helping students to write analytically: do you PEE? How about PEARL? Or PETER? PETEETER? What about EPLWE?

My personal journey through this quagmire is of interest, at least to me, because it highlights some important issue related to my progress as a teacher of English and to the teaching of the subject in general. In this post, I want to survey the different methods for structuring analytical writing that I have used, listing the reasons why, thus far, I have been dissatisfied with all of them. Through this, I hope to uncover some fundamental reasons why all of the above – and more – are unfit for purpose, and why a different approach to the teaching of analytical writing is required.

Much of this post, in particular the ‘different approach’ to analytical writing just mentioned, has been influenced – or borrowed wholesale – from David Didau’s ‘The Learning Spy’ blog, as well as his book ‘The Secret of Literacy’. Specific posts will be highlighted below, but just to give credit where due.

A (brief) survey of analytical writing method to date

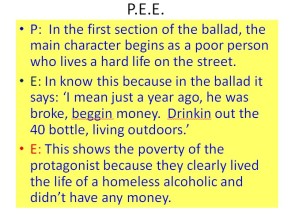

Point, Evidence, Explain (P.E.E)

I started, as I imagine many new English teachers did – before they knew any better – with good old reliable P.E.E. For those who aren’t haven’t heard of this, students make a point, answering a question about a text; give evidence, by quoting a line from the text; and then ‘explain’ the link between the evidence and the point.

Pros:

- P.E.E is easy to remember. With the faint scent of urea adding a minor frisson, students are able to remember the acronym easily which, I suppose, means that they are able to learn how to use the structure more quickly.

- If followed to the letter, PEE is really easy to do, which might make it an appropriate tool for those beginning to learn about how to write analytically.

- It cross cuts schools, and subjects, more of which will be discussed below.

Cons:

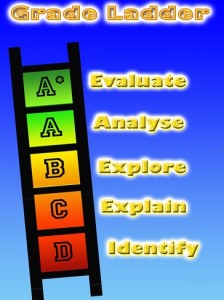

- It is far too easy, lacking in the necessary rigour and detail to make students into expert analytical writers. When you think about it, asking a student merely to explain the link between the evidence and the point is hardly all there is to writing analytically. Where is the fine-grained detail? Where can the student explore the nuances of language? The grade ladder below demonstrates that if students merely ‘explain’ the links between their evidence and their point this is – I think at most –a C grade response.

This leads to the next problem.

- For any teacher who uses PEE for anyone other than students who have never written analytically before, you quickly realize that asking students to ‘explain’ is not enough. (For a different argument for the same view, see Reflecting English’s excellent post on the subject.) For that reason, the term ‘explain’ is then expanded to include language analysis, evaluation of writer’s intention and effect on reader, and a whole raft of other tools.

- This means that P.E.E quickly loses any ‘sticky’ benefits mentioned above: students don’t only need to remember P.E.E, but in actual fact a whole list of other procedures when analysing language

- For those of us who struggle to get students to really understand what command terms mean (explain, explore, analyse etc.,), this is perpetrating a fairly large scale confusion of the term ‘explain’. Using P.E.E is a catch-22: if we take the basic meaning of the term ‘explain’, then P.E.E is not fit for purpose as it only really allows a very basic level of analysis. If we expand it, then we are misusing it with potentially damaging consequences if students are asked to ‘explain’ something in another context or possibly an exam.

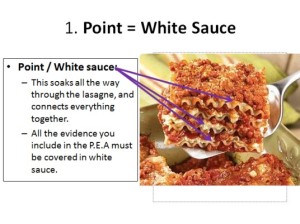

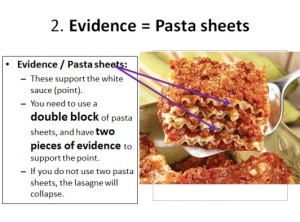

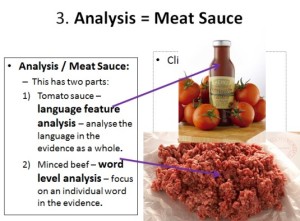

P.E.A Lasagna

In a brief and possibly slightly confused attempt to supplant P.E.E, in my NQT year I devised the P.E.A Lasagna method of analytical writing. To be fair to it, the year 10 English Language group that I used it with did well in their exams, however I did not pursue this approach into my third year as a teacher. Please see the below images for an explanation of the approach. I developed this to help students improve in a few key areas:

- The point / white sauce idea came from the fact that students were not linking back to their point in the rest of their paragraph. They would write the point, and then go off on the tangent. The idea here was that this should remind them that they should always be making links back to the central point

- The ‘double-blocking’ of the pasta sheets/evidence was because I wanted students to be inserting multiple short sections of the text in their paragraphs, rather than simply having one large chunk at the start

- Finally, I wanted students to attempt to attempt to pick quotations apart in their analysis, hence the language features / words split.

Pros:

- Compared to P.E.E, this is a lot more rigorous in its requirements of the students. Unadulterated, it allows for higher achievement than if students simply followed the basic P.E.E structure to the letter.

Cons:

- Although at the time I thought this was easy to remember, I have since changed my mind. While my students did get the hang of it, I’m not sure the silly metaphor helped in this regard, and it potentially distracted students from the key learning, especially before lunch.

- A central problem for this method is that it is not universal; a really good analytical writing method should cross-cut across all subjects, with only minor changes. This could never be used in any subject bar English. If students are to get really expert at analysis, as with any area of know-how, they should be putting this to use across the curriculum.

Finally: PETER, EPLWE, PEARL and the rest

Since my early flirtations with the two above methods, I have used a whole raft of other tools, all of which suffer from many of the pitfalls described above.

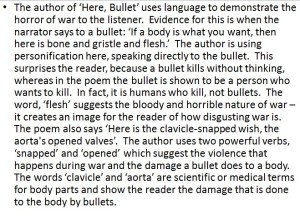

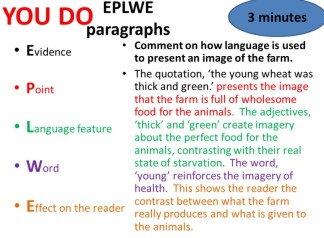

EPLWE (Evidence, Point, Language, Word, Effect) was developed for a particular exam (Edexcel Literature) in which – according to an examiner’s report – it seemed as if students were required to write lots of short, shallow paragraphs rather than anything with any depth

Pros:

- For this, it worked. Students were able to churn these out at around one every three minutes.

Cons:

- It resulted in a situation where students were using one type of analytical writing method in literature, another in language and yet another in history. Not ideal.

- It also had two Es, explain and effect, which made it difficult to learn.

The same can be said for PETER (Point, Evidence, Technique, Explain, Reader response) and PEARL (Point, Evidence, Analysis, Reader Response, Link). Both of these have their good points and, to be fair to them, students have and will continue to perform well in examinations using these methods. But – and this is a big but – none of the above are really fit for purpose. I will recap the reasons why:

- Most rely on a confused and erroneous use of command terms, leading potentially to student error

- Most are only suitable for one small area of our own subject, sometimes only for one exam. As such, students are never in a position to develop a level of comfort and expertise

- Apart from PEE, which I have seen used on other subjects, none of the above are truly suitable for other academic areas that require analysis of evidence, such as history.

- And finally, the most damaging reason of all: anyone who “does” analysis professionally, i.e., academics, journalists and so on, do not use any of the above methods. As such, all of them are gross over-simplifications and are symptomatic of a production line, low expectations approach to teaching. If we really want students who are good at our subject, we should be teaching them to analyse language as a “junior version” of how it is done in the real world, by experts.

The solution

After reading the following blog posts by David Didau (@learningspy), here and here, I am now convinced that there is another way, a way that avoids many of the issues listed above. For the last 6 months, I have been putting this into practice with my students.

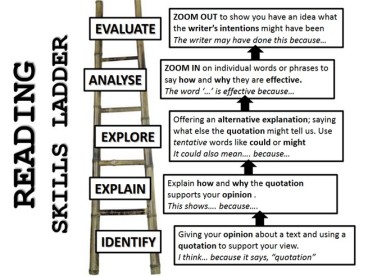

The method requires students to work through a list of five key areas as they write, speak and think about language. These areas, again in a visual created by Didau, are pictured below:

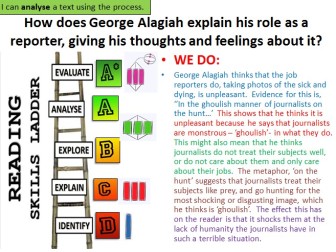

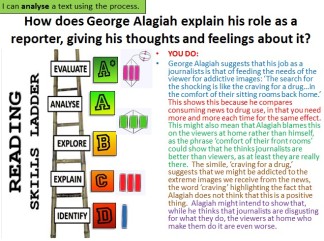

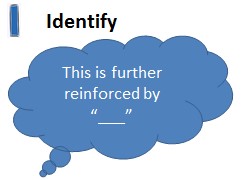

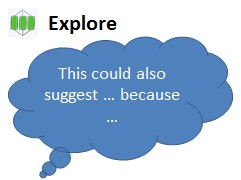

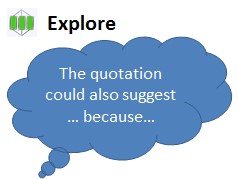

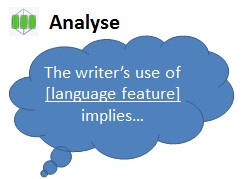

Students begin by ‘identifying’ their answer to the question and providing some evidence for their opinion. They then ‘explain’ the link between their evidence and opinion. So far so P.E.E. Following this, students enter the world of real life academic English by of ‘exploring’ tentative alternative explanations for their evidence. Next, they pick and ‘analyse’ specific elements of language, before finally ‘evaluating’ the links to context by looking at writer’s intention and reader effect.

Here are some examples of my students’ early attempts to use this method:

Pros:

- This method is challenging and rigorous, requiring a high level of knowledge about the text that students are analysing. They must know language features and word meanings, have a wide-ranging knowledge of the context of the text and most importantly understand the text well. This is a good thing.

- This approach – or at least so I think – would be suitable for any subject where students write analytically. The point is that there are different areas of knowledge that come to bear in analysis, and this method asks them to use them all. As such, whether students are analysing a poem or a historical source, they can still apply this procedure.

- Command terms are used accurately.

- While going through each level, each time might not be quite what an academic does when looking at a text, I think that, broadly, this is much more in line with an “expert” approach to analysis. It is training students, albeit at a lower level, to become comfortable with an approach to analysis that could take them to university and beyond.

- Finally, it allows a stepped approach to the teaching of analytical writing. When first becoming familiar with the idea of giving an opinion about a text and supplying evidence, students can use only the first few levels. They can progress up the scale as they become more familiar with the different areas of knowledge required at each.

Cons:

- This is not the easiest approach to remember, although using Didau’s idea of zooming-in and zooming-out really does help. It does need constant practice to get right, and, as such, introducing students to it just before a big exam might not be a good idea. I think they need a while to get it right.

- This is not the kind of method where you can get students writing analytically early on in your study of a text – or at least not with any great success. Students need to build up a strong knowledge base of language techniques, contextual information and detailed knowledge of the text itself before they can hope master it.

- On its own, this does not do enough to help the students build an advanced analytical vocabulary. To combat this, I have created a set of sentence starters that fit within each area, as well as different words that students can use instead of ‘shows’ and ‘suggests’. I provide a small set of examples of above, although the full set can be downloaded here: Analytical Writing Stems

These are just a small selection of the whole group, which I have arranged around my classroom so that students can look around and choose different ways to phrase their analysis. Those with a sharp eye might also spot that I have related each level to the SOLO taxonomy. Controversial, I know, but this links with the way that I like to discuss students’ acquisition and use of knowledge in my lessons. I should also note that, while I have no link to give, these were influenced by an idea of The Learning Spy’s shared at a CPD event.

The idea with this is that not only are students engaging in an analysis that is varied in the areas of knowledge it uses, but also that they are phrasing this in a sophisticated way. An absolutely fantastic blog post from Reflecting English that deals with many similar issues to this can be found here.

What about the skills-knowledge debate?

As far as I am concerned, teaching students this – and any other – method of analysis as a “skill” is a waste of time. As I mentioned above, this method is ineffective if students are not equipped with the requisite knowledge about the particular text(s) that they will be analysing. A recent, excellent post on this subject, found here on Chris Hildrew’s ‘Teaching: Leading Learning’ blog put it in a way that I like: this, and many other things like it, is not a skill but ‘know-how’. To again purloin some ideas from David Didau, teaching students an analytical writing method is an example of ‘procedural’ rather than ‘propositional’ (fact-based) knowledge – a difference only of degree, however. Students can learn how to follow this particular system, and this knowledge will serve them well, but only if they pair this with some – much more important – factual knowledge of language and the text itself. For a vastly clearer discussion of this topic, please see the two posts above.

And again, for download, here are my Analytical Writing Stems.

Thanks for reading.

#1 by teachingbattleground on March 17, 2015 - 10:15 pm

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

#2 by Lisa Edwards on April 26, 2016 - 7:50 am

Reblogged this on Classroom Explorers ~ Lisa Edwards and commented:

An interesting read and approach to analytical writing.